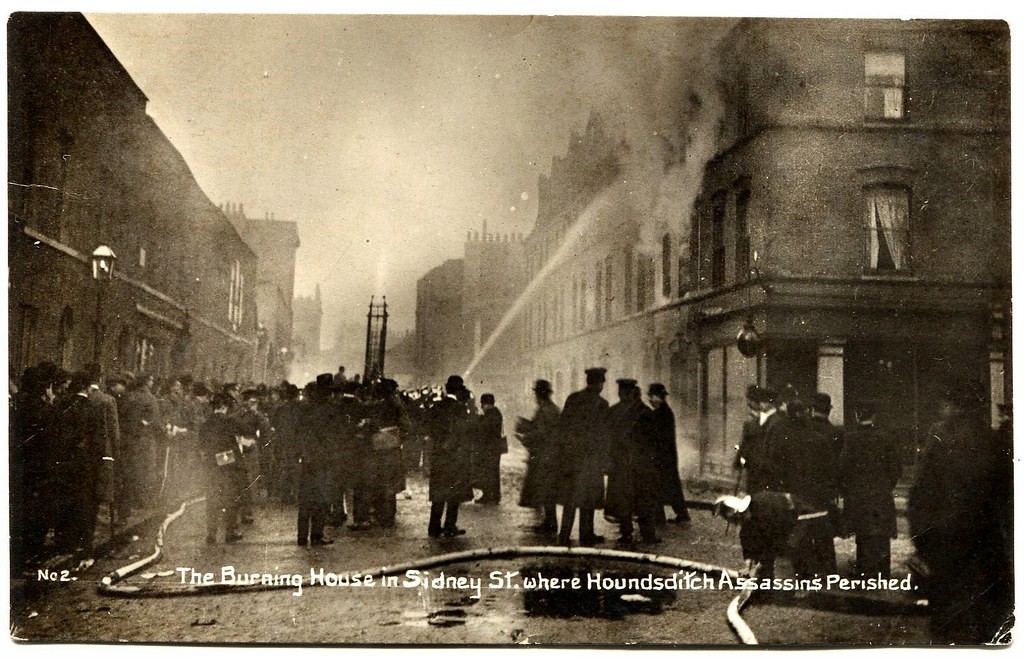

The Siege of Sidney Street on 3 January 1911 is a well known event in London’s history, in which two armed Russian anarchists – one believed to be known as Peter the Painter – took refuge in a house at 100 Sidney Street, Stepney who, together with others, had murdered three City of London policemen a fortnight earlier while robbing a jewellers shop in Houndsditch.

Winston Churchill, the then Home Secretary, attended this incident together with a party of Scots Guards. What is not generally known is the role of the London Fire Brigade during this incident.

As the Metropolitan and City Police laid siege to the house the LFB had been aware of the unfolding events at Sidney Street prior to a fire call being received to this street as messages began to come into Headquarters from the East End. Earlier in the day a local fire officer was sent to ask the police if the Brigade could be of assistance. It was thought that cold water under pressure from large fire jets from covered positions might perhaps drive the men out, in the knowledge that such means had been known to have the desired effect when dealing with troublesome persons attacking the police. However, a message was received that matters were far too dangerous for the Brigade to be of any assistance at this point, so messages continued to be monitored; it had not been anticipated however that there was the possibility of a fire breaking out.

The call came in at 1.03pm from the street fire alarm at Trinity Almshouses, Mile End Road, near the northern end of Sidney Street (actuated by the police who required a fire brigade presence). This conveyed nothing however, since whenever a large crowd collects there was always the possibility of someone pulling a street fire alarm. The predetermined attendance of a horsed escape and steamer from No. 31 Stn Mile End (Sub Officer W.H.Drew) and a steamer from No. 30 Stn Bethnal Green (Station Officer A.E.Edmonds) went on and, on arrival, it was clear the incident was in Sidney Street. The first arriving crews were led to believe, by the police, that they were smoking out burglars and an “Alarm Caused” (no action required by the Brigade) message was initially sent back by Sub Officer Drew at 1.09pm by telephone from the fire alarm point. However, further investigation indicated this was not the case and that a house was on fire. Station Officer Edmonds now sought to tackle this fire but was informed by a police inspector he could not approach the fire. Concerned to carry out his duty but unaware armed men were in the house, he initially insisted on being allowed access to the building and, after remonstrating with the police inspector, was referred to Mr Churchill, who explained that it was too dangerous to approach the building and instructed him to stand by until the gunmen had been dealt with. Station Officer Edmonds then had his crews set into a hydrant and lay out hose in preparation.

A message was received at Headquarters from Station Officer Edmonds at 1.20pm:

“It’s a house of six rooms in Sidney Street alight, shots are being exchanged between troops and the occupants of the house, and the Brigade are not allowed to approach the building to extinguish the fire”.

Given the serious nature of the incident Divisional Officer (North) A.R.Dyer from Northern Division HQ Euston, Superintendent W.R.Canning and District Officer C.E.Pearson from “C” District HQ Whitechapel and Assistant Divisional Officer (North) C.C.B.Morris, Officer of the Day at Brigade HQ Southwark, immediately went on.

ADO Morris, later to become Chief Officer of the Brigade in the 1930s, takes up the story in his book “Fire!” describing the scene on his arrival:

“As I arrived at the fire, I was met by one of the largest crowds I have ever seen – thickly jammed masses of humanity. It looked as though the whole of East London must be there. I had to force my car through a crowd at least 200 feet deep in a small street, and as I emerged into the cleared space I was met with a most amazing sight. A company of Guards were lying about the street as far as possible under cover, firing intermittently at the house, from which bursts of fire were coming from automatic pistols.

I was told to report to Mr Winston Churchill as he was in charge of operations. His order to me was “Stand by and don’t approach the fire until you receive further orders”.

While being duly thankful for this order, I never can understand why the then Home Secretary took executive charge of a situation requiring the most careful handling, as between the police and fire brigade, and as we shall see in a moment, he gave me a wrong order.

Had I been a more experienced officer, I should have taken orders from nobody – advice from the police, yes, under the conditions, but orders, definitely no. At a fire in London the Chief Officer of the LFB or his representative is granted by Act of Parliament absolutely full plenary powers. There can be no officer who has such a wide authority under normal peacetime conditions, and this authority is very necessary at times when immediate decisions have to be made involving the protection of perhaps millions pounds worth of property (this was Station Officer Edmond’s position earlier).

After receiving this order I took stock of the position. The front rooms on the first and second floors were starting to emit dense clouds of smoke, which shortly turned to flames. The firing from the house was gradually ceasing. Shortly afterwards the flames reached the roof, which blazed up, the fire spreading to the adjoining roofs, this being one a row of terraced houses. By this time we in the Brigade were to say the least getting somewhat restless. How far would the fire spread before we could start to attack it? The LFB Superintendent kept urging me to do something, but the Home Secretary was a very important dignitary to a junior officer, so I sat tight while the fire continued to spread.

The houses all had a projecting back addition containing two rooms. As the front windows had been broken by shots before the fire started, the draft from the fire had carried it to the front and in all probability the back two rooms were intact. No sooner had we realised what we might be up against – a burst of firing from the back of the house as soon as we approached it – than the order came “You can now approach the fire”. (it is thought these were the last shots fired by the anarchists). So up we dashed with our lines of hose, through adjoining property to the back of the house followed by Mr.Wensley of the Metropolitan Police and we found the rooms absolutely intact, not even filled with smoke. Fortunately by that time the criminals were no longer in a position to fire on us. As we made our way through the back of the house the order was given to turn on the water.

While our party approached the back, another hoseline was taken along the side of the street, up an adjoining house and on to the roof to attack the fire from above. By this time the house was well alight. The fire had travelled right down to the ground floor and the roofs of the houses on each sided had caught. In a few minutes the fire would have spread right along Sidney Street along both sides of the house we were attacking.

As soon as water came through the hose we started to work our way into the ground floor where we soon extinguished the fire. Both the upper floors were burnt through and the house was almost a shell as far as the front was concerned. Shortly afterwards Mr.Wensley followed us in and there only remained the search for bodies. While searching the building for the bodies of the anarchists and standing on the ground floor examining an automatic pistol which District Officer Pearson had just discovered, we heard a crash and found both ourselves lying on the floor covered with debris. On freeing myself I found Pearson could not move and a hearthstone, which had fallen from the second floor, was lying between us. Beyond a badly dented helmet, I was uninjured and he was the unlucky one. His spine had been fractured by this stone. He lingered on for six months, paralysed in both legs, and then died. He was promoted to Superintendent shortly after his accident.

We found two charred bodies in the debris, one of them had been shot through the head and the other had apparently died of suffocation. At the inquest a verdict of justifiable homicide was returned. Much discussion took place afterward as to what caused the fire. Did the anarchists deliberately set the building alight, thus creating a diversion to enable them to escape? The view of the London Fire Brigade at the time was that a gas pipe was punctured on one of the upper floors, and that the gas was lighted either at the time of the bullet piercing it or perhaps afterwards by a bullet causing a spark which ignited the escaping gas”.

During the inquest there was some implied criticism of the Brigade’s actions in not tackling the fire soon enough, suggesting the anarchists were left to their fate. Station Officer Edmonds explained what had happened. It seems there was some effort to keep Winston Churchill’s participation in the background, the police taking responsibility, but Mr. Churchill attended on the third day and admitted he ordered the Brigade not to advance lest they be shot.

As well as District Officer Pearson five other members of the Brigade were injured by the falling debris: Divisional Officer A.R.Dyer, who also later became Chief Officer in the 1920s, Superintendent W.R.Canning, Supt “C” District, and Firemen V.H O’Grady, W.E.Sampson and W.E.Hodges. All eventually returned to duty except Superintendent Pearson, who was transferred from London Hospital to the British Home and Hospital for Incurables, Crown Lane, Streatham on 9 March and died there on 9 July, being buried in a private ceremony at Highgate Cemetery on 13 July. He was aged 42 with 22 years service in the LFB and left a widow and three children.

Due to the developing fire situation ADO Morris had requested four additional steamers (23 Homerton, 32 Bow, 38 Kingsland and 37 Shoreditch) and the eventual LFB attendance was two horsed escapes (31 Mile End and 34 Shadwell) and nine engines with 52 men, the “Stop” message (Stop mobilising-no further assistance required) was sent at 2.45pm.